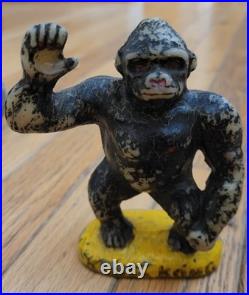

1960s KING KONG Wind Up Toy by MARX Nice RARE See Video! + wax figure

1960s KING KONG Wind Up Toy by MARX Nice RARE - See Video! This listing is for a vintage KING KONG made by Marx Toys in the 1960s.

This scarce and desirable toy is the wind up version of the large battery operated King Kong by Marx. Cooper, and a legal battled flared up in early 1960s when Toho studios wanted to license King Kong for two movies. A rare and desirable monster toy, King Kong stands approximately 7 inches tall and is made of tin with faux fur, plastic head/hands, and a wind up motor. Wind up is tiht but winds and gorilla falls over or some reason and chain is missing.

The wax King Kong gorilla measures approximately 5 in height. King Kong, also referred to simply as Kong, is a fictional giant monster resembling a gorilla, who has appeared in various media since 1933. The character has since become an international pop culture icon, [18] appearing in several movies, comics, videogames and television series, as well as repeatedly crossing over with the Godzilla franchise. Kong has been dubbed the King of the Beasts. [19] His first appearance was in the novelization of the 1933 film King Kong from RKO Pictures, with the film premiering a little over two months later.

A sequel quickly followed that same year with The Son of Kong, featuring Little Kong. The Japanese film company Toho later produced King Kong vs.

In 1976, Dino De Laurentiis produced a modern remake of the original film directed by John Guillermin. A sequel, King Kong Lives, followed a decade later featuring a Lady Kong. Another remake of the original, set in 1933, was released in 2005 by filmmaker Peter Jackson. Kong: Skull Island (2017), set in 1973, is part of Warner Bros. Pictures and Legendary Entertainment's Monsterverse, which began with a reboot of Godzilla in 2014. Kong was released in 2021. It was followed by the film Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire in 2024, which featured more of Kong's kind. King Kong has inspired a number of imitators, parodies, cartoons, books, comics, video games, theme park rides, and a stage play. [20] King Kong has also crossed over into other franchises, such as Planet of the Apes, [21] and encountered characters from other franchises in crossover media, such as pulp characters Doc Savage and Tarzan, and the Justice League.[22] His role in the different narratives varies, ranging from an egregious monster to a tragic antihero. Overview King Kong graphics at the Empire State Building The King Kong character was conceived and created by American filmmaker Merian C. In the original film, the character's name is Kong, a name given to him by the inhabitants of the fictional "Skull Island" in the Indian Ocean, where Kong lives along with other oversized animals, such as plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, and various dinosaurs. An American film crew, led by Carl Denham, captures Kong and takes him to New York City to be exhibited as the "Eighth Wonder of the World". Kong escapes and climbs the Empire State Building, only to fall from the skyscraper after being attacked by weaponized biplanes.

Denham comments, "It wasn't the aeroplanes, it was beauty killed the beast", for he climbs the building in the first place only in an attempt to protect Ann Darrow, an actress originally kidnapped by the natives of the island and offered up to Kong as a sacrifice (in the 1976 remake, her character is named "Dwan"). A pseudo-documentary about Skull Island that appears on the DVD for the 2005 remake (originally seen on the Sci-Fi Channel at the time of its theatrical release) gives Kong's scientific name as Megaprimatus kong[23] ("Megaprimatus", deriving from the prefix "mega-" and the Latin words "primate" and "primatus", means "big primate" or "big supreme being") and states that his species may be related to Gigantopithecus, but that genus of giant ape is more closely related to orangutans than to gorillas. Conception and creation Merian C. Cooper glances up at his creation.

Cooper became fascinated by gorillas at the age of six. [24] In 1899, he was given a book from his uncle called Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa. [25] The book, written in 1861, chronicled the adventures of Paul Du Chaillu in Africa and his various encounters with the natives and wildlife there. [26] Cooper became fascinated with the stories involving the gorillas, in particular, Du Chaillu's depiction of a particular gorilla known for its "extraordinary size", [27] that the natives described as "invincible" and the "King of the African Forest". [28] When Du Chaillu and some natives encountered a gorilla later in the book he described it as a "hellish dream creature" that was "half man, half beast".

[29] As an adult, Cooper became involved in the motion picture industry. While filming The Four Feathers in Africa, he came into contact with a family of baboons. [30] This gave him the idea to make a picture about primates. [31] A year later when he got to RKO, Cooper wanted to film a "terror gorilla picture". As the story was being fleshed out, Cooper decided to make his gorilla giant sized.[32] He came up with the ending before the rest of the story as he stated: "Without any conscious effort of thought I immediately saw in my mind's eye a giant gorilla on top of the building". [33] Cooper also was influenced by Douglas Burden's accounts of the Komodo dragon, [34] and wanted to pit his terror gorilla against dinosaur-sized versions of these reptiles, stating to Burden: I also had firmly in mind to giantize both the gorilla and your dragons to make them really huge. However I always believed in personalizing and focusing attention on one main character and from the very beginning I intended to make it the gigantic gorilla, no matter what else I surrounded him with.

[34] Around this time, Cooper began to refer to his project as a "giant terror gorilla picture" featuring "a gigantic semi-humanoid gorilla pitted against modern civilization". [35] When designing King Kong, Cooper wanted him to be a nightmarish gorilla monster. As he described Kong in a 1930 memo: His hands and feet have the size and strength of steam shovels; his girth is that of a steam boiler. This is a monster with the strength of a hundred men.

But more terrifying is the head-a nightmare head with bloodshot eyes and jagged teeth set under a thick mat of hair, a face half-beast half-human. [36] Willis O'Brien created an oil painting depicting the giant gorilla menacing a jungle heroine and hunter for Cooper, [37][38] but when it came time for O'Brien and Marcel Delgado to sculpt the animation model, Cooper decided to backpedal on the half-human look for the creature and became adamant that Kong be a gorilla. O'Brien on the other hand, wanted him to be almost human-like to gain audience empathy, and told Delgado to "make that ape almost human".

[39] Cooper laughed at the end result, saying that it looked like a cross between a monkey and a man with very long hair. [39] For the second model, O'Brien again asked Delgado to add human features but to tone it down somewhat.

The end result (which was rejected) was described as looking like a missing link. [39] Disappointed, Cooper stated, I want Kong to be the fiercest, most brutal, monstrous damned thing that has ever been seen!

"[39] In December 1931, Cooper got the dimensions of a bull gorilla from the American Museum of Natural History telling O'Brien, "Now that's what I want! [39] When the final model was created, it had the basic look of a gorilla but managed to retain some human-like qualities. For example, Delgado streamlined the body by removing the distinctive paunch and rump of a gorilla.

[40] O'Brien would incorporate some characteristics and nuances of an earlier creature he had created in 1915 for the silent short The Dinosaur and the Missing Link into the general look and personality of Kong, even going as far as to refer to the creature as "Kong's ancestor". [41][42] When it came time to film, Cooper agreed that Kong should walk upright at times (mostly in the New York sequences) in order to appear more intimidating. Cooper said he was very fond of strong, hard-sounding words that started with the letter "K". Some of his favorite words were "Komodo", "Kodiak" and "Kodak". [44] When Cooper was envisioning his giant terror gorilla idea, he wanted to capture a real gorilla from the Congo and have it fight a real Komodo dragon on Komodo Island (this scenario would eventually evolve into Kong's battle with the tyrannosaur on Skull Island when the film was produced a few years later at RKO).Cooper's friend Douglas Burden's trip to the island of Komodo and his encounter with the Komodo dragons was a big influence on the Kong story. [45] Cooper was fascinated by Burden's adventures as chronicled in his book Dragon Lizards of Komodo where he referred to the animal as the "King of Komodo".

[44] It was this phrase along with "Komodo" and "Kongo" [sic] (and his overall love for hard sounding "K"-words)[46] that gave him the idea to name the giant ape "Kong". He loved the name, as it had a "mystery sound" to it. After Cooper got to RKO, British mystery writer Edgar Wallace was contracted to write the first draft of the screen story. It was simply referred to as "The Beast".

RKO executives were unimpressed with the bland title. Selznick suggested Jungle Beast as the film's new title, [47] but Cooper was unimpressed and wanted to name the film after the main character. He stated he liked the "mystery word" aspect of Kong's name and that the film should carry "the name of the leading mysterious, romantic, savage creature of the story" such as with Dracula and Frankenstein. [47] RKO sent a memo to Cooper suggesting the titles Kong: King of Beasts, Kong: The Jungle King, and Kong: The Jungle Beast, which combined his and Selznick's proposed titles.

[47] As time went on, Cooper would eventually name the story simply Kong while Ruth Rose was writing the final version of the screenplay. Selznick thought that audiences would think that the film, with the one word title of Kong, would be mistaken as a docudrama like Grass and Chang, which were one-word titled films that Cooper had earlier produced, he added the "King" to Kong's name in order to differentiate it. [48] Appearances and abilities In his first appearance in King Kong (1933), Kong was a gigantic prehistoric ape.[49] While gorilla-like in appearance, he had a vaguely humanoid look and at times walked upright in an anthropomorphic manner. [43] Like most simians, Kong possesses semi-human intelligence and great physical strength. Kong's size changes drastically throughout the course of the film. Cooper envisioned Kong as being "40 to 50 feet tall", [50] animator Willis O'Brien and his crew built the models and sets scaling Kong to be only 18 feet (5.5 m) tall on Skull Island, and rescaled to be 24 feet (7.3 m) tall in New York.

[51] This did not stop Cooper from playing around with Kong's size as he directed the special effect sequences; by manipulating the sizes of the miniatures and the camera angles, he made Kong appear a lot larger than O'Brien wanted, even as large as 60 feet (18.3 m) in some scenes. As Cooper said in an interview: I was a great believer in constantly changing Kong's height to fit the settings and the illusions.

He's different in almost every shot; sometimes he's only 18 feet tall and sometimes 60 feet or larger. This broke every rule that O'Bie and his animators had ever worked with, but I felt confident that if the scenes moved with excitement and beauty, the audience would accept any height that fitted into the scene. For example, if Kong had only been 18 feet high on the top of the Empire State Building, he would have been lost, like a little bug; I constantly juggled the heights of trees and dozens of other things. The one essential thing was to make the audience enthralled with the character of Kong so that they wouldn't notice or care that he was 18 feet high or 40 feet, just as long as he fitted the mystery and excitement of the scenes and action. [52] Concurrently, the Kong bust made for the film was built in scale with a 40-foot (12.2 m) ape, [53] while the full sized hand of Kong was built in scale with a 70-foot (21.3 m) ape. [54] Meanwhile, RKO's promotional materials listed Kong's official height as 50 feet (15.2 m). [49] In the 1960s, Toho Studios from Japan licensed the character for the films King Kong vs. Godzilla and King Kong Escapes. (See below) In 1975, Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis paid RKO for the remake rights to King Kong. This resulted in King Kong (1976). This Kong was an upright walking anthropomorphic ape, appearing even more human-like than the original. Also like the original, this Kong had semi-human intelligence and vast strength.In the 1976 film, Kong was scaled to be 42 feet (12.8 m) tall on Skull island and rescaled to be 55 feet (16.8 m) tall in New York. [55] Ten years later, Dino De Laurentiis got the approval from Universal to do a sequel called King Kong Lives. This Kong had more or less the same appearance and abilities, but tended to walk on his knuckles more often and was enlarged, scaled to 60 feet (18.3 m). [56] Universal Studios had planned to do a King Kong remake as far back as 1976. They finally followed through almost 30 years later, with a three-hour film directed by Peter Jackson.

Jackson opted to make Kong a gigantic silverback gorilla without any anthropomorphic features. This Kong looked and behaved more like a real gorilla: he had a large herbivore's belly, walked on his knuckles without any upright posture, and even beat his chest with his palms as opposed to clenched fists. In order to ground his Kong in realism, Jackson and the Weta Digital crew gave a name to his fictitious species Megaprimatus Kong and suggested it to have evolved from the Gigantopithecus. Kong was the last of his kind. He was portrayed in the film as being quite old, with graying fur and battle-worn with scars, wounds, and a crooked jaw from his many fights against rival creatures.

He is the dominant being on the island, the king of his world. Like his film predecessors, he possesses considerable intelligence and great physical strength and also appears far more nimble and agile. This Kong was scaled to a consistent height of 25 feet (7.6 m) tall on both Skull Island and in New York. [57] Jackson describes his central character: We assumed that Kong is the last surviving member of his species.

He had a mother and a father and maybe brothers and sisters, but they're dead. He's the last of the huge gorillas that live on Skull Island... There will be no more. He's a very lonely creature, absolutely solitary. It must be one of the loneliest existences you could ever possibly imagine.Every day, he has to battle for his survival against very formidable dinosaurs on the island, and it's not easy for him. He's carrying the scars of many former encounters with dinosaurs. I'm imagining he's probably 100 to 120 years old by the time our story begins. And he has never felt a single bit of empathy for another living creature in his long life; it has been a brutal life that he's lived.

[58] In the 2017 film Kong: Skull Island, Kong is scaled to be 104 feet (31.7 m) tall, [59] making it the second largest and largest American incarnation in the series until the 2021 film Godzilla vs. Kong, in which he became the largest incarnation in the series, standing at 337 feet (102.7 m). [60][61] Director Jordan Vogt-Roberts stated in regard to Kong's immense stature: The thing that most interested me was, how big do you need to make [Kong], so that when someone lands on this island and doesn't believe in the idea of myth, the idea of wonder - when we live in a world of social and civil unrest, and everything is crumbling around us, and technology and facts are taking over - how big does this creature need to be, so that when you stand on the ground and you look up at it, the only thing that can go through your mind is: That's a god! [62] He also stated that the original 1933 look was the inspiration for the design: We sort of went back to the 1933 version in the sense that he's a bipedal creature that walks in an upright position, as opposed to the anthropomorphic, anatomically correct silverback gorilla that walks on all fours.

Our Kong was intended to say, like, this isn't just a big gorilla or a big monkey. This is something that is its own species. It has its own set of rules, so we can do what we want and we really wanted to pay homage to what came before... And yet do something completely different, and if anything, our Kong is meant to be a throwback to the'33 version. I don't think there's much similarity at all between our version and Peter [Jackson]'s Kong.That version is very much a scaled-up silverback gorilla, and ours is something that is slightly more exaggerated. A big mandate for us was, "How do we make this feel like a classic movie monster"? [63] Co-producer Mary Parent also stated that Kong is still young and not fully grown as she explains that "Kong is an adolescent when we meet him in the film; he's still growing into his role as alpha". [64] Ownership rights While one of the most famous movie icons in history, King Kong's intellectual property status has been questioned since his creation, featuring in numerous allegations and court battles. The rights to the character have always been split up with no single exclusive rights holder.

Cooper created King Kong, he assumed that he owned the character, which he had conceived in 1929, outright. Cooper maintained that he had only licensed the character to RKO for the initial film and sequel, but had otherwise owned his own creation.

In 1935, Cooper began to feel something was amiss when he was trying to get a Tarzan vs. King Kong project off the ground for Pioneer Pictures (where he had assumed management of the company). Selznick suggested the project to Cooper, the flurry of legal activity over using the Kong character that followed-Pioneer had become a completely independent company by this time and access to properties that RKO felt were theirs was no longer automatic-gave Cooper pause as he came to realize that he might not have full control over this product of his own imagination after all.

[65] Years later in 1962, Cooper found out that RKO was licensing the character through John Beck to Toho studios in Japan for a film project called King Kong vs. Cooper had assumed his rights were unassailable and was bitterly opposed to the project. In 1963 he filed a lawsuit to enjoin distribution of the movie against John Beck, as well as Toho and Universal the film's U.

[66] Cooper discovered that RKO had also profited from licensed products featuring the King Kong character such as model kits produced by Aurora Plastics Corporation. Cooper's executive assistant, Charles B. FitzSimons, said that these companies should be negotiating through him and Cooper for such licensed products and not RKO.

In a letter to Robert Bendick, Cooper stated: My hassle is about King Kong. I created the character long before I came to RKO and have always believed I retained subsequent picture rights and other rights. Many people vouched for Cooper's claims, including David O.

Selznick, who had written a letter to Mr. Loewenthal of the Famous Artists Syndicate in Chicago in 1932 stating (in regard to Kong), The rights of this are owned by Mr. Ayelsworth the then-president of the RKO Studio Corp. And a formal binding letter from Mr.

Kahane also a former president of RKO Studio Corp. Confirming that Cooper had only licensed the rights to the character for the two RKO pictures and nothing more. [68] Without these letters, it seemed Cooper's rights were relegated to the Lovelace novelization that he had copyrighted (he was able to make a deal for a Bantam Books paperback reprint and a Gold Key comic adaptation of the novel, but that was all that he could do). Cooper's lawyer had received a letter from John Beck's lawyer, Gordon E.

Cooper or anyone else to define Mr. Cooper's rights in respect of King Kong. His rights are well defined, and they are non-existent, except for certain limited publication rights. [69] In a letter addressed to Douglas Burden, Cooper lamented: It seems my hassle over King Kong is destined to be a protracted one. They'd make me sorry I ever invented the beast, if I weren't so fond of him! Makes me feel like Macbeth: "Bloody instructions which being taught return to plague the inventor". [69] The rights over the character did not flare up again until 1975, when Universal Studios and Dino De Laurentiis were fighting over who would be able to do a King Kong remake for release the following year. [70] When Universal got wind of this, they filed a lawsuit against RKO, claiming that they had a verbal agreement from them regarding the remake.During the legal battles that followed, which eventually included RKO countersuing Universal, as well as De Laurentiis filing a lawsuit claiming interference, Colonel Richard Cooper (Merian's son and now head of the Cooper estate) jumped into the fray. [72] Richard Cooper then filed a cross-claim against RKO claiming that, while the publishing rights to the novel had not been renewed, his estate still had control over the plot/story of King Kong.

[71] In a four-day bench trial in Los Angeles, Judge Manuel Real made the final decision and gave his verdict on November 24, 1976, affirming that the King Kong novelization and serialization were indeed in the public domain, and Universal could make its movie as long as it did not infringe on original elements in the 1933 RKO film, [73] which had not passed into the public domain. [74] Universal postponed their plans to film a King Kong movie, called The Legend of King Kong, for at least 18 months, after cutting a deal with Dino De Laurentiis that included a percentage of box office profits from his remake.

[75] However, on December 6, 1976, Judge Real made a subsequent ruling, which held that all the rights in the name, character, and story of King Kong (outside of the original film and its sequel) belonged to Merian C. This ruling, which became known as the "Cooper judgment", expressly stated that it would not change the previous ruling that publishing rights of the novel and serialization were in the public domain. It was a huge victory that affirmed the position Merian C. Cooper had maintained for years.

In 1980 Judge Real dismissed the claims that were brought forth by RKO and Universal four years earlier and reinstated the Cooper judgement. [76] In 1982 Universal filed a lawsuit against Nintendo, which had created an impish ape character called Donkey Kong in 1981 and was reaping huge profits over the video game machines. [74] While they had a majority of the rights, they did not outright own the King Kong name and character. [78] The courts also pointed out that the Kong rights were held by three parties: RKO owned the rights to the original film and its sequel. The Dino De Laurentiis company (DDL) owned the rights to the 1976 remake.

Richard Cooper owned worldwide book and periodical publishing rights. [77] The judge then ruled that "Universal thus owns only those rights in the King Kong name and character that RKO, Cooper, or DDL do not own".

This amounted to a wanton and reckless disregard of Nintendo's rights. Second, Universal did not stop after it asserted its rights to Nintendo. It embarked on a deliberate, systematic campaign to coerce all of Nintendo's third party licensees to either stop marketing Donkey Kong products or pay Universal royalties.Finally, Universal's conduct amounted to an abuse of judicial process, and in that sense caused a longer harm to the public as a whole. Universal's assertions in court were based not on any good faith belief in their truth, but on the mistaken belief that it could use the courts to turn a profit. They were ordered to pay fines and all of Nintendo's legal costs from the lawsuit. That, along with the fact that the courts ruled that there was simply no likelihood of people confusing Donkey Kong with King Kong, [77] caused Universal to lose the case and the subsequent appeal.

Since the court case, Universal still retains the majority of the character rights. [further explanation needed] In 1986 they opened a King Kong ride called King Kong Encounter at their Universal Studios Tour theme park in Hollywood (which was destroyed in 2008 by a backlot fire), and followed it up with the Kongfrontation ride at their Orlando park in 1990 (which was closed down in 2002 due to maintenance issues). They also finally made a King Kong film of their own, King Kong (2005). In the summer of 2010, Universal opened a new 3D King Kong ride called King Kong: 360 3-D at their Hollywood park, replacing the destroyed King Kong Encounter.

[81] In July 2016, Universal opened a new King Kong attraction called Skull Island: Reign of Kong at Islands of Adventure in Orlando. [82] In July 2013, Legendary Pictures made an agreement with Universal to market, co-finance, and distribute Legendary's films for five years starting in 2014 and ending in 2019, the year that Legendary's similar agreement with Warner Bros. Pictures was set to expire.

One year later, at San Diego Comic-Con, Legendary announced (as a product of its partnership with Universal), a King Kong origin story, initially titled Skull Island, with Universal distributing. [83] After the film was retitled Kong: Skull Island, Universal allowed Legendary to move to Warner Bros.

[84] so they could do a King Kong and Godzilla crossover film (in the continuity of the 2014 Godzilla movie), since Legendary still had the rights to make more Godzilla movies with Warner Bros. Before their contract with Toho expired in 2020. [85][86] Richard Cooper, through the Merian C.

Cooper Estate, retained publishing rights for the content that Judge Real had ruled on December 6, 1976. In 1990, they licensed a six-issue comic book adaptation of the novelization of the 1933 film to Monster Comics, and commissioned an illustrated novel in 1994 called Anthony Browne's King Kong.

In 2013, they became involved with a musical stage play based on the story, called King Kong: The Eighth Wonder of the World which premiered that June in Australia[87][88] and then on Broadway in November 2018. [89] The production is involved with Global Creatures, the company behind the Walking with Dinosaurs arena show. [90] In 1996, artist/writer Joe DeVito partnered with the Merian C.Cooper estate to write and/or illustrate various publications based on Merian C. Cooper's King Kong property through his company, DeVito ArtWorks, LLC. Through this partnership, DeVito created the prequel/sequel story Skull Island on which DeVito based a pair of original novels relating the origin of King Kong: Kong: King of Skull Island and King Kong of Skull Island. In addition, the Cooper/DeVito collaboration resulted in an origin-themed comic book miniseries with Boom! Studios, [91] an expanded rewrite of the original Lovelace novelization, Merian C.

Cooper's King Kong (the original novelization's publishing rights are still in the public domain), and various crossovers with other franchises such as Doc Savage, Tarzan[92] and Planet of the Apes. [21] In 2016, DeVito ArtWorks, through its licensing program, licensed its King Kong property to RocketFizz for use in the marketing of a soft drink called King Kong Cola, [93] and had plans for a live action TV show co-produced between MarVista Entertainment and IM Global. [94] Other products that have been produced through this licensing program include Digital Trading Cards, [95] Board Games, [96] a Virtual Reality Arcade Game, [97] a remake of the original King Kong Glow-In-The-Dark Model Kit, [98] and a video game developed by IguanaBee called Skull Island: Rise of Kong.[99] In April 2016, Joe DeVito sued Legendary Pictures and Warner Bros. Producers of the film Kong: Skull Island, for using elements of his Skull Island universe, which he claimed that he created and that the producers had used without his permission. [100] Devito partnered with Dynamite Entertainment to produce comic books and board games based on the property, [101] resulting in the comic book series called King Kong: The Great War published in May 2023. [102] In 2022, DeVito had partnered with Disney to produce a live-action series tentatively called King Kong that explores the origin story of Kong.

The series is slated to stream on Disney+. Stephany Folsom is attached to write the series and to be executive produced by James Wan via his production company Atomic Monster. [103] RKO (whose rights consisted of only the original film and its sequel) signed over the North American, Latin American and Australian distribution rights to its film library to Ted Turner's Turner Entertainment in a period spanning 1986 to 1989. Following a series of mergers and acquisitions, Warner Bros.

Family Entertainment released the direct-to-video animated musical film The Mighty Kong, which re-tells the plot of the original 1933 film. Nineteen years later, Warners co-produced the film Kong: Skull Island and in 2021 co-produced the film Godzilla vs. Kong, after Legendary Pictures brought the projects over from Universal[104] to build up the MonsterVerse. Kong director Adam Wingard, the rights to the character may have also been transferred to Warner Bros. [105] DDL (whose rights were limited to only their 1976 remake) did a sequel in 1986 called King Kong Lives (but they still needed Universal's permission to do so). [106] Today most of DDL's film library is owned by StudioCanal, which includes the rights to these two films.[citation needed] Toho incarnations The two depictions of Kong in the Toho films In the 1960s, Japanese studio Toho licensed the character from RKO and produced two films that featured the character, King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) and King Kong Escapes (1967). Toho's interpretation of King Kong as a kaiju, [107] differed greatly from the original in size and abilities.

Among kaiju, King Kong was suggested to be among the most powerful in terms of raw physical force, possessing strength and durability that rivaled that of Godzilla. As one of the few mammal-based kaiju, Kong's most distinctive feature was his intelligence. He demonstrated the ability to learn and adapt to an opponent's fighting style, identify and exploit weaknesses in an enemy, and utilize his environment to stage ambushes and traps. [108] In King Kong vs.

Godzilla, Kong was scaled to be 45 m (148 ft) tall. This version of Kong was given the ability to harvest electricity as a weapon and draw strength from electrical voltage.[109] In King Kong Escapes, Kong was scaled to be 20 m (66 ft) tall. This version was more similar to the original, where he relied on strength and intelligence to fight and survive.

[110] Rather than residing on Skull Island, Toho's version of Kong resided on Faro Island in King Kong vs. Godzilla and on Mondo Island in King Kong Escapes. In 1966, Toho planned to produce Operation Robinson Crusoe: King Kong vs. Ebirah as a co-production with Rankin/Bass Productions, but Ishiro Honda was unavailable at the time to direct the film and, as a result, Rankin/Bass backed out of the project, along with the King Kong license. [111] Toho still proceeded with the production, replacing King Kong with Godzilla at the last minute and shot the film as Ebirah, Horror of the Deep.Elements of King Kong's character remained in the film, reflected in Godzilla's uncharacteristic behavior and attraction to the female character Daiyo. [112] Toho and Rankin/Bass later negotiated their differences and co-produced King Kong Escapes in 1967, loosely based on Rankin/Bass' animated show.

Toho Studios wanted to remake King Kong vs. Godzilla, which was the most successful of the entire Godzilla series of films, in 1991 to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the film, as well as to celebrate Godzilla's upcoming 40th anniversary, but they were unable to obtain the rights to use Kong, and initially intended to use Mechani-Kong as Godzilla's next adversary. [113] It was soon learned that even using a mechanical creature who resembled Kong would be just as problematic legally and financially for them. As a result, the film became Godzilla vs.

King Ghidorah, with one last failed attempt made to use Kong in 2004's Godzilla: Final Wars. [114] Appearances Main article: King Kong (franchise) Film Film Release date Director(s) Story by Screenwriter(s) Producer(s) Distributor(s) King Kong March 2, 1933 Merian C. Schoedsack[115] Edgar Wallace and Merian C. Cooper[115] James Creelman and Ruth Rose[115] Merian C.

Schoedsack[115] RKO Pictures[115] Son of Kong December 22, 1933 Ernest B. Schoedsack Ruth Rose Ernest B.

Godzilla August 11, 1962 Ishiro Honda[1] (Japan) Thomas Montgomery[116] U. Shinichi Sekizawa[1] (Japan) Paul Mason and Bruce Howard[116] U. Tomoyuki Tanaka[1] (Japan) John Beck[116] U. [117] (Japan) Universal International[117] U. King Kong Escapes July 22, 1967 Ishiro Honda Arthur Rankin Jr. Takeshi Kimura Tomoyuki Tanaka and Arthur Rankin Jr. King Kong December 17, 1976 John Guillermin Lorenzo Semple Jr.Dino De Laurentiis Paramount Pictures King Kong Lives December 19, 1986 Ronald Shusett and Steven Pressfield Martha Schumacher De Laurentiis Entertainment Group King Kong December 14, 2005 Peter Jackson Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens and Peter Jackson Jan Blenkin, Carolynne Cunningham, Fran Walsh and Peter Jackson Universal Pictures Kong: Skull Island March 10, 2017 Jordan Vogt-Roberts John Gatins Dan Gilroy, Max Borenstein, and Derek Connolly Thomas Tull, Jon Jashni, Alex Garcia and Mary Parent Warner Bros. Kong March 24, 2021 Adam Wingard Terry Rossio, Michael Dougherty, and Zach Shields Eric Pearson and Max Borenstein Thomas Tull, Jon Jashni, Brian Rogers, Mary Parent, Alex Garcia, and Eric McLeod[118] Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire March 29, 2024 Terry Rossio, Adam Wingard, and Simon Barrett[119] Terry Rossio, Simon Barrett, and Jeremy Slater[119] Television Four television shows have been based on King Kong: The King Kong Show (1966), Kong: The Animated Series (2000), Kong: King of the Apes (2016), and Skull Island (2023). [120] A live-action series based on Joe DeVito's King Kong Of Skull Island franchise is in development for Disney+, written by Stephany Folsom and executive produced by James Wan via Atomic Monster. [103] King Kong appeared in episode 27 of the anime show The New Adventures of Gigantor titled King Kong vs Tetsujin (?????? This episode aired April 10 1981, and featured King Kong battling the giant robot hero Gigantor.

In the story it turns out it was just a robot disguised as King Kong. [121] The character appears in the final episode of season one of the television series Monarch: Legacy of Monsters. [122] Cultural impact Main article: King Kong in popular culture This section may contain irrelevant references to popular culture. Please help improve it by removing such content and adding citations to reliable, independent sources. (October 2018) The DC Comics character Titano the Super-Ape (here seen climbing the Daily Planet building and confronting Superman) appears to be modeled on King Kong. From Superman #138, art by Curt Swan and Stan Kaye. King Kong, as well as the series of films featuring him, have been featured many times in popular culture outside of the films themselves, in forms ranging from straight copies to parodies and joke references, and in media from comic books to video games. The Beatles' 1968 animated film Yellow Submarine includes a scene of the characters opening a door to reveal King Kong abducting a woman from her bed. The Simpsons episode "Treehouse of Horror III" features a segment called "King Homer" which parodies the plot of the original film, with Homer as Kong and Marge in the Ann Darrow role. It ends with King Homer marrying Marge and eating her father.[citation needed] The 2005 animated film Chicken Little features a scene parodying King Kong, as Fish out of Water starts stacking magazines thrown in a pile, eventually becoming a model of the Empire State Building and some plane models, as he imitates King Kong in the iconic scene from the original film. [citation needed] The British comedy TV series The Goodies made an episode called "Kitten Kong", in which a giant cat called Twinkle roams the streets of London, knocking over the British Telecom Tower. [citation needed] The controversial World War II Dutch resistance fighter Christiaan Lindemans-eventually arrested on suspicion of having betrayed secrets to the Nazis-was nicknamed "King Kong" due to his being exceptionally tall.

[123] Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention recorded an instrumental about "King Kong" in 1967 and featured it on the album Uncle Meat. Zappa went on to make many other versions of the song on albums such as Make a Jazz Noise Here, You Can't Do That on Stage Anymore, Vol. 3, Ahead of Their Time, and Beat the Boots.

[citation needed] The Kinks recorded a song called "King Kong" as the B-side to their 1969 "Plastic Man" single. The Kinks recorded a song called "Apeman", with lyric: "I'm a King Kong man, I'm voodoo man, I'm an ape man", a 1970 follow-up single to Lola, both appear on the album Lola Versus Powerman and the Moneygoround, Part One.

In 1972, a 550 cm (18 ft) fiberglass statue of King Kong was erected in Birmingham, England. [citation needed] The second track of The Jimmy Castor Bunch album Supersound from 1975 is titled "King Kong". [124] Filk Music artists Ookla the Mok's "Song of Kong", which explores the reasons why King Kong and Godzilla should not be roommates, appears on their 2001 album Smell No Evil. [citation needed] Daniel Johnston wrote and recorded a song called "King Kong" on his fifth self-released music cassette, Yip/Jump Music in 1983, rereleased on CD and double LP by Homestead Records in 1988.

The song is an a cappella narrative of the original movie's story line. Tom Waits recorded a cover version of the song with various sound effects on the 2004 release, The Late Great Daniel Johnston: Discovered Covered. [citation needed] ABBA recorded "King Kong Song" for their 1974 album Waterloo.

Although later singled out by ABBA songwriters Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus as one of their weakest tracks, [125] it was released as a single in 1977 to coincide with the 1976 film playing in theaters. Tenacious D wrote "Kong" to be released as a bonus track for the Japanese version of The Pick of Destiny to accompany the film. [citation needed] The 1994 Nintendo Game Boy title Donkey Kong features the eponymous character grow to a gargantuan size as the game's final boss.

[1] They made many types of toys including tin toys, toy soldiers, toy guns, action figures, dolls, toy cars and model trains. [2] Some of their notable toys are Rock'em Sock'em Robots, Big Wheel tricycles, Disney-branded dollhouses and playsets based on TV shows like Gunsmoke.

Its products were often imprinted with the slogan One of the many Marx toys, have you all of them? Logo and offerings A child on a Big Wheel in 1973 (Rogers Park, Chicago) The Marx logo was the letters "MAR" in a circle with a large X through it, resembling a railroad crossing sign.

[3] As the X sometimes goes unseen, Marx toys were, and are still today, often misidentified as "Mar" toys. [citation needed] Reputedly, because of this name confusion, the Italian diecast toy company Martoys, after two years of production, changed its name to Bburago in 1976.

The Big Wheel, which was introduced in 1969, is enshrined in the National Toy Hall of Fame. Marx's toys included tinplate buildings, tin toys, toy soldiers, playsets, toy dinosaurs, mechanical toys, toy guns, action figures, dolls, dollhouses, toy cars and trucks, and HO-scale and O-scale trains. Marx also made several models of typewriters for children. Marx's less expensive toys were extremely common in dime stores, and its larger, costlier toys were staples for catalog and department store retailers such as Eaton's, Gamages, Sears, W.Penney and Spiegel especially around Christmas. [4] History A 1930 Marx ad for a No. Initially, after working for Ferdinand Strauss, Marx, born in 1894, was a distributor with no manufacturing capacity. All product production would have to be contracted out for the first few years.

Another success was the "Mouse Orchestra" with tinplate mice on piano, fiddle, snare, and one conducting. [8] Marx listed six qualities he believed were needed for a successful toy: familiarity, surprise, skill, play value, comprehensibility and sturdiness. [9] By 1922, both Louis and David Marx were millionaires. Initially, Marx reevaluated and produced a few original toys by predicting the hits and manufacturing them less expensively than the competition. The yo-yo is an example: although Marx is sometimes wrongly credited with inventing the toy, the company was quick to market its own version.

[6] Unlike most companies, Marx's revenues grew during the Great Depression, with the establishment of production facilities in economically hard-hit industrial areas of Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and England. He was declared "Toy King of the World" in October 1937 in a London newspaper. By 1938, Marx employed 500 workers in the Dudley factory and 4000 in the American factories.

[6] Marx was the star article of the magazine with his picture displayed on the front cover. Marx was the initial inductee in the Toy Industry Hall of Fame, and his plaque proclaimed him "The Henry Ford of the toy industry". An O Gauge Marx lithographed train set made in the late 1940s to early 1950s At its peak, Louis Marx and Company operated three manufacturing plants in the United States: Erie, Pennsylvania, Girard, Pennsylvania, and Glen Dale, West Virginia. [6] In 1952 Marx Company stationary listed operations in: Mexico, London England, Swansea Wales, Durbin South Africa, Sydney Australia, Toronto Canada, São Paulo Brazil and Paris France. By 1959, the demand for American toys was a billion dollars a year.

[12] Marx enjoyed his wealth at his 20.5-acre estate in the wealthy suburb of Scarsdale, north of New York City. The estate featured a 25-room Georgian mansion, a barn and stables for horses he raised and other amenities. [13] Playsets Among the most enduring Marx creations were a long series of boxed "playsets" throughout the 1950s and 1960s based on television shows and historical events. These include "Roy Rogers Rodeo Ranch" and Western Town, "Walt Disney's Davy Crockett at the Alamo", "Gunsmoke", "Wagon Train", "The Rifleman Ranch", "The Lone Ranger Ranch", "Battle of the Blue and Grey", "The Revolutionary War" (including "Johnny Tremain"), "Tales of Wells Fargo", "The Untouchables", "Robin Hood", "The Battle of the Little Big Horn", "Arctic Explorer", "Ben Hur", "Fort Apache", "Zorro", "Battleground", "Tom Corbett Training Academy", "Prehistoric Times", and many others.[14] Playsets included highly detailed plastic figures and accessories, many with some of the toy world's finest tin lithography. This pricing formula adhered to the Marx policy of "more for less" and made the entire series attainable to most customers for many years. Original sets are highly prized by baby boomer collectors to this day. [15][page needed] Marx produced dollhouses from the 1920s into the 1970s. In the late 1940s Marx began to produce metal lithographed dollhouses with plastic furniture (at the same time it began producing service stations).

These dollhouse were variations of the Colonial style. An instant sensation was the "Disney" house, featured in the 1949 Sears catalogue. The popularity of Marx dollhouses gained momentum, and up to 150,000 Marx dollhouses were produced in the 1950s.

Two house sizes were available, with two different size furniture to match; the most popular in the 1/2" to 1' scale, and the larger 3/4" to 1' scale. An L-shaped ranch hit the market in 1953, followed by a split-level of 1958. As the space race heated up, Marx playsets reflected the obsession with all things extraterrestrial such as "Rex Mars", "Moon Base", "Cape Canaveral", and "IGY International Geophysical Year", among other space themed sets. In a similar theme, Marx also capitalized on the robot craze, producing the Big Loo, "Your friend from the Moon", and the popular Rock'em Sock'em Robots action game. In 1963, Marx began making a series of beatnik style plastic figurines called the Nutty Mads, which included some almost psychedelic creations, such as Donald the Demon - a half-duck, half-madman driving a miniature car.These were similar to the counterculture characters of other companies introduced about a year before, such as Revell's Rat Fink by "Big Daddy" Ed Roth, or Hawk Models' "Weird-Ohs", designed by Bill Campbell. The trains were called Joy Line.

[16] These were small four inch tinplate cars with a small windup or electric engine. Marx acquired the Woods company in 1934, although his brand appears on floor trains, trolleys, Joy Line and the M10000 sets, years before the acquisition.This was the beginning of Marx trains. [17] In 1934 Marx produced its first newly designed model train set, the streamlined Union Pacific M-10000. [18] The streamlined Marx Commodore Vanderbilt was issued in 1935 with new 6 inch tinplate cars. The ever popular Marx Canadian Pacific 3000 appeared in 1936 in Canada, while the articulated Marx Mercury was introduced to America. The success of Marx "027" train line forced other manufacturers to follow suit in size and fashion.

Marx continued to make tinplate train sets until 1972. Plastic sets began in 1952 and only plastic sets were made after 1973, until the end of the company in 1975.

[19] Overtaking Lionel Marx Tin Litho Train Tunnels-014 Even though Marx trains never held the prestige of Lionel's trains, they were able to outsell them for most of the late fifties. [6] When it comes to quality and quantity, Louis Marx and Company is considered "the most important producer of inexpensive American toy trains". [22] Toy soldier sets Marx is well known by collectors and some kids for making good quality toy soldiers. These sets were often known as''Battleground'', offering Germans and Americans.Though there also were Pacific sets, which had Japanese soldiers and combat planes, such as the Zero. Some of their most popular sets were''Navarone'' (based on the film),''Iwo Jima'',''The Alamo'' (basing on the film) and more sets based in movies and series, such as The Gallant Men, specially in John Wayne and the films he was in. Vehicles Pre-war Cast iron was unwieldy, heavy, and not well-suited to proper detail or model proportions and gradually it was replaced by pressed tin. [23] Marx offered a variety of tin vehicles, from carts to dirigibles - the company would lithograph toy patterns on large sheets of tinplated steel.

These would then be stamped, die-cut, folded, and assembled. [24] Marx was long known for its car and truck toys, and the company would take small steps to renew the popularity of an old product.In the 1920s, an old truck toy that was falling behind in sales was loaded with plastic ice cubes and the company had a new hit. [6] The Honeymoon Express, a wind-up train on track with a plane circling above, later became the Mickey Mouse Express and then the Subway Express. Popeye pushing a barrel of spinach eventually became the 1940 Tidy Tim Street Cleaner and Charlie McCarthy in his "Benzine Buggy". [24][3] A Marx police motorcycle from the 1940s Some of the most popular vehicles were Crazy Cars like the Funny Flivver of 1926 - another was the eloping "Joy Riders".

[25] One earlier and much sought after tin toy was an open Amos'n Andy Ford Model T four door, as well as another Model T with driver apparently on a European jaunt and hauling a trunk at the rear with the names of various European cities on it. This model was produced in a variety of liveries. One toy, the Tricky Taxi seems to have had origins in a Heinrich Muller toy from Nuremberg in Germany. [10] The 1935 G-Man pursuit car was possibly the largest vehicle Marx ever made at 14½ inches long. [3] Even doll houses, gasoline stations, parking lots and street scenes were made in tin.

[3] That Marx was doing well even in the depression is shown by the date of introduction of their well-known motorcycle cop toy - 1933. [27] A number of tinplate trucks, buses and vans were made in the 1930s, particularly in the latter part of the decade. Trucks were made, particularly Studebakers, in a variety of colors and formats, and often advertised in Sears catalogues.

[28] These included several different series like the truck hauling five tinplate "stake bed" trailers, a "dumping" garbage truck, many variations on larger truck "car carriers" hauling different vehicles, and a set of completely chromed trucks. Lumar toys "Lumar Lines" was another name used for a line of floor operated tin toys, trucks, vehicles, trains beginning in the early 1930s, in the United States and England.

Production continued after WWII with the "Friendship" train that honored the real train that had sent supplies from the United States to England in 1947. The "standard gauge" floor train was first marketed in 1933 under the "Girard Model Works" moniker. [29] Plastics Louis Marx and Company was an early player in the plastic toy field.[30] After World War II Marx introduced more vehicles, taking advantage of molding techniques with various plastics. Pressed tin and steel remained in the form of Buicks, Nashes, or other semi-futuristic sedans, race cars, and trucks that didn't replicate any actual vehicles. One car was a tin Buick-like wood-bodied station wagon. These were often of various larger sizes, ranging from 10 to 20 inches long.

Some vehicles were difficult to identify as Marx; one had to look for the small "X-in-O" logo, usually on the lower rear of the vehicle. Often there were no markings on the base. More and more, however, plastic models appeared in a variety of sizes, three series of which are significant. The first series, in 1950, included inexpensive 4-inch replicas of early 1950s cars, both foreign and domestic, like Talbot, Volkswagen, Jaguar, Studebaker, Ford, Chevrolet, GMC Van and others.

They were supplied as accessories for Marx' large tinplate gas station or rail station toys. These were molded of polystyrene and came with die-cast metal wheel-and-axle combinations. The second series was identical, except for updating the cars to 1954 models. The third series, released in 1959, included updated models of 1959 cars, only these were molded in polyethylene and had polyethylene wheels/axles, and were supplied with an updated 1959 gas station. The Marx 1959 gas station cars were downsized and simplified versions of AMT and Jo-Han flywheel models.In the early 1950s, one Marx product line showed a greater sophistication in toy offerings. The "Fix All" series was introduced, whose main attraction was larger plastic vehicles (about 14 inches long) that could be taken apart and put back together with included tools and equipment. A 1953 Pontiac convertible (erroneously identified on packaging as a sedan), and a 1953 Mercury Monterey station wagon which featured an articulated drive-line. Everything from the pistons to the crankshaft to the rear axle gears were visible through clear plastic, and wood-trim decals for the sides finished off this marvelous model.

A very large 1953 Chrysler convertible, a 1953 Jaguar XK120 roadster, a WWII-era Willys Jeep, a Dodge-ish utility truck, a tow truck, a tractor, a larger scale motorcycle, a helicopter, and a couple of airplanes were all part of the Fix All series. The cars' boxes boasted features like "Over 50 parts" and For a real mechanic!

As an example, the tow truck came with cast metal box and open wrenches, an adjustable end wrench, a two-piece jack, gas can, hammer, screwdriver, and fire extinguisher. The Jeep came with a star wrench, a screw jack and working lights.

Since the 1950s, Marx had factories in different locations. Among these was a factory in Swansea, Wales, which made a variety of toys for the British market. Example of some of the plastic cars made there were Motorway Station Wagons which looked like late 1950s U. Fords, a remote control 1950 Pontiac, and a Ford Zephyr wagon police car.The Marx factory was in the same industrial estate as the Corgi Toys factory. [31] The Marx Hudson 13" toy In 1948, the Hudson Motor Car Company made a detailed in-house promotional model of its "step down 4-door Commodore for exclusive use by their dealers. The model was exceptionally well done, and came in four authentic two-tone color combos, but sadly, was never available on the retail market.

Some sources erroneously insist this model was made by Marx, [32] but in fact, it was Hudson's own production effort, manufactured, produced and assembled in Hudson's main factory. [33][34] Soon after, Marx fabricated an injection mold of Hudson's more precise model and marketed this simplified version as a more inexpensive mechanized toy. It was available as a police car in grass green or a fire chief car in bright red.

The clear windows of the original were replaced with a single, stamped metal piece with lithographed images of cartoonish policemen or firemen. The police version even had a shotgun protruding through the windshield.

With batteries an oversize roof light lit up and the gun made a corny rat-a-tat sound. Not one of Marx's more successful toys, their Hudson was large and unwieldy, being aimed at pre-teens. After newer, more modern American cars appeared, the Marx Hudson quickly became obsolete, resulting in an oversupply on retail toy shelves. Other autos This section does not cite any sources.

Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Marx also made Studebaker and Packard vehicles especially through the 1930s and 1940s. They often appeared with the Studebaker badge logo in a very promotional way, though evidence of Marx as a promotional provider is uncertain. One of Marx's later Studebakers was an Avanti with a dented fender that could be replaced with a'repaired' one, which was odd, as the real Avanti had a fiberglass body - and would not dent. A 1948 Packard Fire Chief's car was one that looked, in theme, much like the step-down Hudson. The'Electric Marx-Mobile' pedal car Into the 1960s and 1970s, Marx still made some cars, though increasingly these were made in Japan and Hong Kong. Especially impressive were two-foot long "Big Bruiser" tow trucks with Ford C-Series cabs and "Big Job" dump trucks, a T-bucket hot rod of the same large size and some foreign cars like a Jaguar SS100, which was later reissued. Marx made some 1/25 scale slot cars, like a Jaguar XKE remote control convertible. Into the 1970s, Marx jumped on several bandwagons, for example, plastic pull string funny cars of typical 1:25 scale model size, but this was not quick enough to save the company.Marx sometimes joined with European toy makers, putting their name on traditional European toys. For example, about 1968, Solido and Marx made a deal to sell these French metal die cast models in the U. With the Marx name added to the box. The boxes were, for the most part, regular red Solido boxes with the Marx "x-in-o" logo and "by Marx" directly below the Solido script.

Nowhere on the cars did the Marx name appear. The small scale market During the 1960s Marx offered its Elegant Models, a collection of Matchbox-like 1930s to 1950s style race cars in red and yellow boxes.

Also offered were airplanes, trucks, and, in the same series, metal animals boxed in a similar style. Some of the vehicles from this era were marketed under the Linemar or Collectoy names.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Marx tried to compete not only with Matchbox, but with Mattel Hot Wheels, making small cars with thin axle, low-friction wheels. These were marketed, not too successfully, under a few different names. One of the most common was "Mini Marx Blazers" with "Super Speed Wheels". The cars were made in a slightly smaller scale than Hot Wheels, often 1:66 to about 1:70.Proportions of these cars were simple, but accurate, though details were somewhat lacking. [35] Some cars, however, included such niceties as a driver behind the wheel. While some of the earlier toys had a simpler Tootsietoy style single casting, newer cars were colored in bright chrome paints with decals and fast axle wheels.

Tires were plain black with thin whitewalls. The reason to make Linemar toys in Japan was to keep costs down. Under the Linemar name, Marx produced The Flintstones and other licensed toy vehicles.

[37] Quaker also owned the Fisher-Price brand, but struggled with Marx. Quaker had hoped Marx and Fisher-Price would have synergy, but the companies' sales patterns were too different. The company was also faulted for largely ignoring the trend towards electronic toys in the early 1970s.

Dunbee-Combex-Marx era Like many toy makers, Dunbee-Combex-Marx struggled with high interest rates and an economic slowdown. By 1979, most US operations were ceased, and by 1980, the last Marx plant closed in West Virginia. [38] The Marx brand disappeared and Dunbee-Combex-Marx filed for bankruptcy. [39] Toy legacy This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section.

(September 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Some popular Marx tooling is still used today to produce toys and trains. A company called Marx Trains, Inc.

Produced lithographed tin trains, both of original design and based on former Louis Marx patterns. Plastic O scale train cars and scenery using former Marx molds were previously produced by MDK and are now marketed under the "K-Line by Lionel" brand name. Model Power produces HO scale trains from old Marx molds.

The Big Wheel rolls on, as a property of Alpha International, Inc. (Cedar Rapids, Iowa), which has been acquired by J. Mattel reintroduced Rock'em Sock'em Robots around 2000 (albeit at a smaller size than the original). Marx's toy soldiers and other plastic figures are in production today in Mexico, and in the US for the North American market and are mostly targeted at collectors, although they sometimes appear on the general consumer market.

[40] In 2001, a longtime collector of Marx toys, Francis Turner, established the Marx Toy Museum in Moundsville, West Virginia, near the old Glen Dale plant, to display toys from his collection and inform visitors about the history and output of the company and its founder. However, over its decade and a half of operation, the museum's income could not sustain maintenance of a physical facility, and it was closed permanently on June 30, 2016. [41] The collection has only been shown on loan to other museums and through a "virtual museum" website, which was on sale since the start of the year 2021.

[42] In 2019, Jay Horowitz of American Classic Toys, and current rights holder of the Marx brands, entered into an exclusive license agreement with The Juna Group to represent the Marx brands in all categories outside of toys and playthings, worldwide.